Music review: Nduduzo Makhathini's uNomkhubulwane

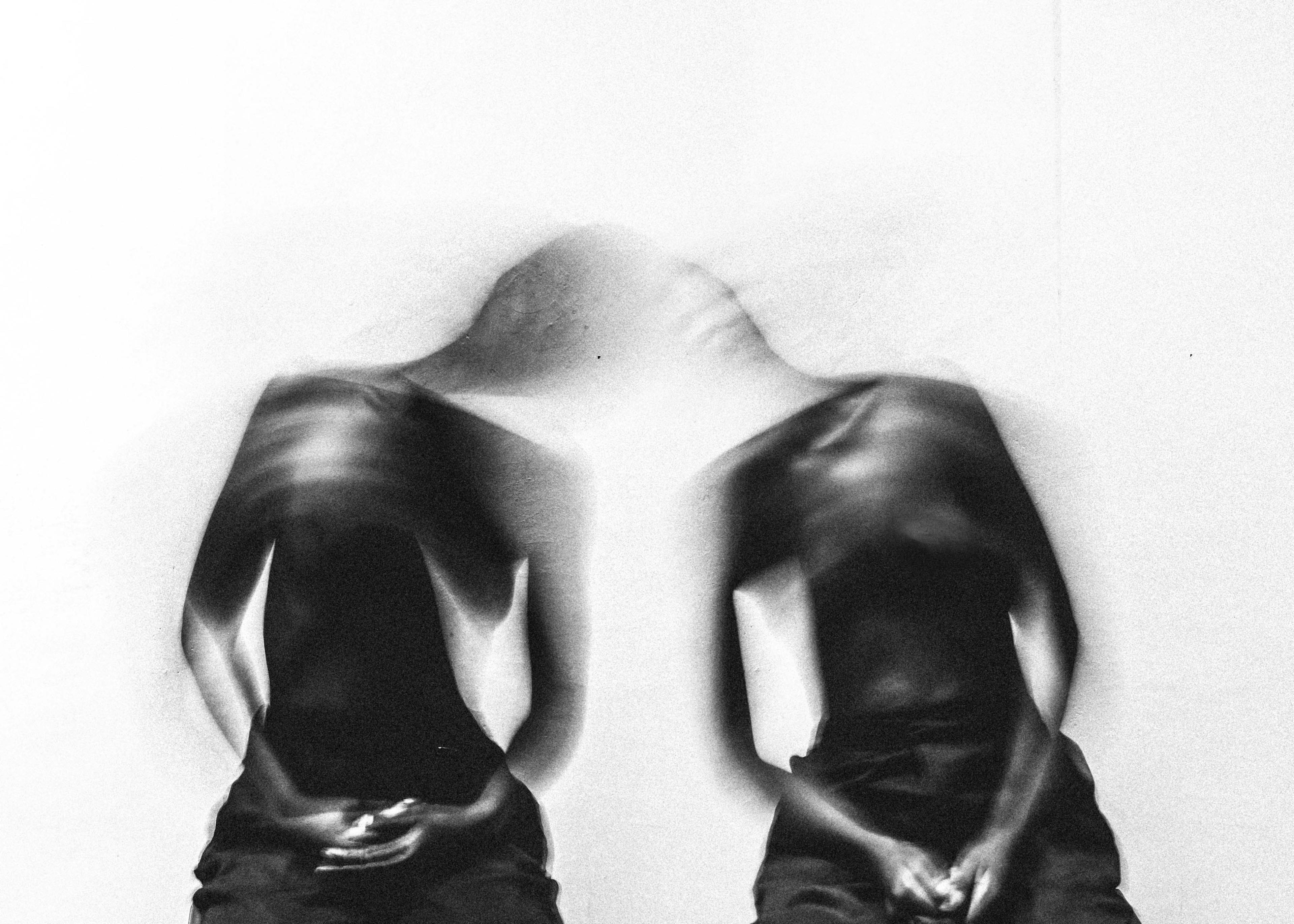

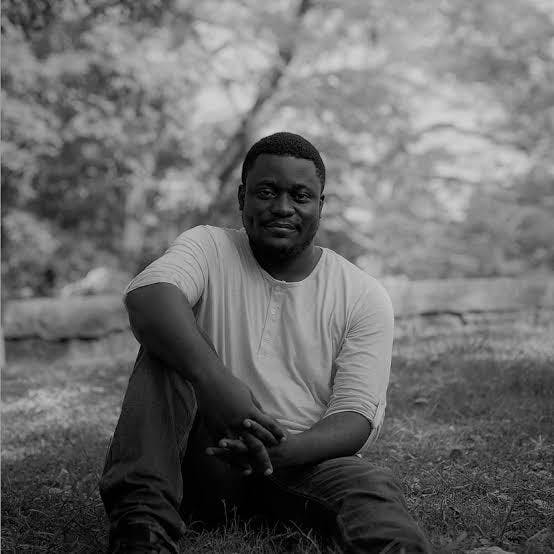

South African jazz pianist, composer, educator and healer Nduduzo Makhathini's third studio album uNomkhubulwane exemplifies an emerging movement in South African jazz of artists seeking a musical restoration of indigenous worldviews, writes Milisuthando Bongela.

To understand the influence that South African pianist, composer, educator, and healer Nduduzo Makhathini has had on the trajectory of jazz in the country in the last decade, one need only look at his collaborators, peers, and siblings in song. That, and his assemblage of credits in the relatively small but wide-reaching cosmogram of contemporary South African music reveal akahambi yedwa—he is not alone.

Take singer-songwriter Msaki. When I interviewed her in Johannesburg in 2019, she credited her relationships with kindred souls like Makhathini for opening her up “to the idea that there are so many ways to access spirit and the intelligence that we have as African people”. Before working with and befriending Makhathini, she harboured an all-too-commonplace fear of iSintu—what we inadequately translate as African spirituality from Nguni languages such as isiZulu—because of the ways Christianity’s “civilising” mission sought to subordinate indigenous worldviews. iSintu, which has homologous terms in the Ntu language family spoken by almost a third of the continent, can refer to spirituality. The root word -ntu is equivalent to “spirit” or “consciousness”, but iSintu signifies more. It is a state and condition of being. iSintu is a system by which Ntu cultures in their many diverse facets, expressions, and contexts mutually reinforce ways of being in and with the world that are relational, intergenerational, and ecological.

Through relationships with peers like Makhathini, Msaki’s music has been moving toward the restitutive act of ukuzilanda—a ritual fetching of one’s self from where you left and were made to leave parts of that self. She is among the ensemble of contemporary South African musicians—among them Linda Sikhakhane, Thandiswa Mazwai, Tumi Mogorosi, Gabi Motuba, Zoë Modiga, Simphiwe Dana, Malcolm Jiyane, Thandi Ntuli, The Brother Moves On, Thabang Tabane, and Sibusile Xaba—who can be considered part of a larger movement of artists posturing towards a collective, organic musical restoration of iSintu. Their genre is South African jazz and jazz-adjacent, but it’s also something more.

In this larger movement, Makhathini plays the of role umondlali—the table-setter who brings the cloth and crockery so that the meal can be served. It’s in the way his piano playing is the foundational element in his own and others’ compositions. It’s also in his role as an educator and a healer. In this latest album, uNomkhubulwane, Makhathini’s third studio release, the alchemy of these roles is evident, and listeners are the blessed diners: umondlali usondlalele.

uNomkhubulwane follows a contained, thematic three-movement structure on what I see as the fate of the Ntu peoples—aBantu. It opens with ‘Libations: Omnyama’, a menu of sorts for what’s to come. The song invites listeners in with a series of spoken and sung prostrations and salutations over staccato piano and heartbeat-like drums in a hypnotic, looping melody. “Siyakhothama manxusa asemkhathini,” Makhathini cries out, inviting the ancestors into space and then addressing them. “Konakele la ekhaya [How abominable things have become here at home],” he declares. This is followed by a demand of the ancestors: “Khanyisani emhlabeni onzima, omagingxigingxi [Bring light to our difficulties in this gruelling world]”. It is a prayer and a surrender to the feminine god Nomkhubulwane, after whom the album is named and who, in Zulu mythology, is the mother of Mvelinqangi, the one who appeared first; the son of the masculine god Nkulunkulu, the greatest of the great creators.

From the first trio of songs, Makhathini pivots to water, a medium that connects the worlds of the living, the ancestors, and the yet-to-be-born. ‘Water Spirits: Izinkonjana’—the slow, languid ballad opening the next section of the album—elicits a form of saudade in me with its palimpsests of the Cape jazz tradition of Zim Ngqawana and Abdullah Ibrahim. I found myself feeling sad and soothed at the same time, imagining the path we, aBantu, have travelled and the one that lies ahead. In that uncertainty, I felt held. But just as I was finding comfort in water, Makhatini, accompanied again by piano licks, drums, and double bass, turns to land through a scanty recalling of battles and torments of Zulu warriors against colonisation. In the album’s final movement, ‘Inner Attainment’, we settle with awareness, abundance, and sacred holiness.

uNomkhubulwane has inserted itself into the traditions of jazz signatures both sonically and conceptually as a soundtrack for what, to me, is the incorruptibility of iSintu as an expression of Blackness: its ability to both resist and surrender to the unfathomable, to face it all, tasting the brute essence of what it means to become and remain a person, umuntu, throughout. But something else is also happening and alive in the album. The sound is experientially rooted in the disclaimer-free sanctification of music that is facing in the directions of south and yesterday. It is concerned with umoya—spirit—and with spirituality. It is concerned with the elemental: ancestry, ritual, violence, cleansing, restitution, healing, and inzolo—the pursuit of peace and silence after violence. These are the elements of the periodic table of the yet undefined genre that uNomkhubulwane exemplifies. With these elements, the genre could be said to be resurrecting cultural, artistic, and spiritual practices once deemed illegal under colonial and apartheid “witchcraft suppression” laws.

Having seen Makhathini live a few times, I found his playing earnest, emotive, and experiential, which, in interviews, the artist has said he’s augmented with improvisation in uNomkhubulwane. What I have sometimes found difficult about these performances, however, are the overtures into explanation. This is evident in the marketing of this latest release. Physical copies of the album come with a companion essay in which Makhathini analyses and interprets the project. I understand the desire to translate the album’s knowledge universe for the outside world— and for the inside world, too, given that historical attempts to subdue iSintu were not entirely unsuccessful. I also understand the desire to share what you’ve learnt, which I imagine Makhathini feels, having done scholarly work on the rich world of Nguni mythology, spirituality, history, and resistance. But the music can be trusted to stand on its own and move listeners in ways words cannot. That was certainly my experience. The album delivered the message with self-possession: indeed we have lost, but we are not lost.